The 45-foot-long great room has a ceiling that may be an imported antiquity and doors to terraces on three sides.

Photo: Eytan Stern Weber/Evan Joseph Images

The developer of the Ritz Tower, a 1926 co-op on the corner of 57th and Park, didn’t give himself the penthouse on the 41st floor — then, the city’s highest residence. Instead, he chose floors 19 and 20, where the building steps inward, with room for a terrace on three sides. Designed by Emery Roth, the king of prewar elegance, the Ritz Tower got an edit from the frothier architects at Carrère and Hastings, who covered the exterior with cartouches, scrolls, and urns. The owner’s terrace has a huge obelisk, and it was Thomas Hastings who personally designed the interiors around a 45-foot-long great room, which he turned into a medieval hall with a bit of Italian palazzo. (A Juliet balcony with columns and arches looks over the room from a gallery on the second floor.) The ceiling is from a 17th-century Venetian palace, according to the listing, and the terrace can be seen through leaded windows and doors freckled with stained glass, some with medieval-style imagery of masks and angels. There’s a wood-burning fireplace, and the wood floors might also be hand-crafted antiques: Hand-carved wooden dowels cover the nails holding down eight-inch-wide slabs of old trees.

The view down the great room north, toward an alcove with a wood-burning fireplace. The embellishment is typical of Thomas Hastings, who designed the interiors for his client, the developer of the Ritz Tower.

Photo: Eytan Stern Weber/Evan Joseph Images

The rest of the apartment feels more like a university club, with three wood-paneled studies — three — one in maple and two in rare pear wood. The built-in shelves pull out, so a curious reader can get a closer view of a title. This is a pretty good clue that the apartment was designed for a man of letters. Arthur Brisbane started out as a reporter known for a spare, straightforward style. He became one of the most popular and well-paid newspapermen of his generation, with syndicated columns titled simply “Today” and “The Week.” The latter ran in 1,200 newspapers, including on the front page of titles run by his boss, publisher William Randolph Hearst, who later partnered with his star on two of Brisbane’s side hustles. First, Brisbane would sniff out dying local papers, buy them himself, Hearst-ify them, and sell them back to his boss. When Hearst got into real estate, building an empire up and down 57th Street, Brisbane followed, and they partnered on flashy projects, including the Ziegfeld Theatre.

On the southern end of the great room, a passage leads to a library where one can easily imagine William Randolph Hearst and Arthur Brisbane swilling scotch.

Photo: Eytan Stern Weber/Evan Joseph Images

But when it came to the corner of 57th and Park, where old-money families owned low, stony mansions, Brisbane went out on his own, buying them up over the years and tapping the Ritz-Carlton to partner with him on its first hotel-residential tower (by then a proven concept). In 1926, when the building opened, the lower floors had traditional hotel rooms. Upper apartments, though, were built without kitchens, since their owners might as well call down for room service. And Brisbane’s personal suite was the only one with a private elevator and the only one with a kitchen.

Coffee cans on the counter add a dose of reality to a fantastical apartment.

Photo: Eytan Stern Weber/Evan Joseph Images

The Ritz Tower drew famous residents almost from the start. There were actresses (Greta Garbo and Deborah Kerr), bankers (James Seligman and George Gustav Heye), and the children of famous families (Rockefellers and Hearst’s own son George). The building went co-op in 1955. And when Neil Simon visited a mentor there, Simon vowed to one day move in. (He eventually owned three units.) Early owners got in trouble for cooking on hotplates, but most have now added kitchens and many have combined the relatively tiny one and two bedrooms of the past into trophy apartments. By 2015, Clive Davis owned five units. Charles Cohen, the real-estate mogul, bought six to create a 7,500-square-foot spread, then bought luxe fashion brands to fill the downstairs retail. Though the building went co-op, it kept the hotel amenities, and the fees reflect this (monthly maintenance is $20,381).

But poor, rich Brisbane never made quite enough to pay down the $4 million mortgage. In 1928, he sold his interests — including the duplex — to Hearst, who lived in his reporter’s former rooms with his mistress, Marion Davies, according to the 2002 report that landmarked the address.

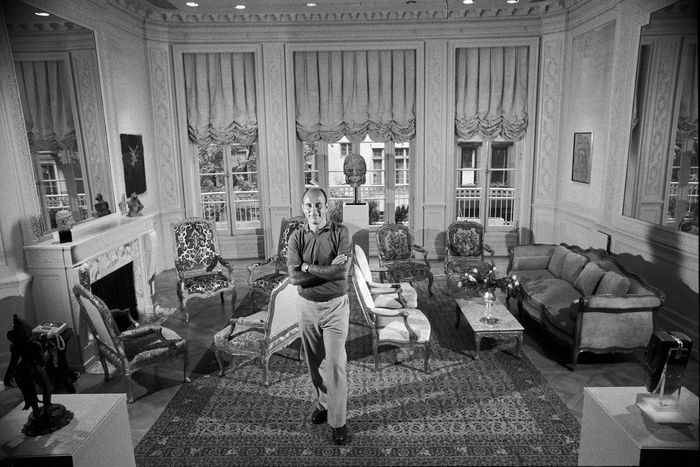

Heller in 1977, surrounded by chairs and antiquities similar to the style of furniture and art in the apartment now.

Photo: Don Hogan Charles/The New York Times/Redux

Ben Heller, an art dealer who was early to buy Pollocks and Rothkos, bought the duplex after selling an apartment on Central Park West in 1975 that he had filled with modern furniture and major artwork. Then his tastes seem to expand: In 1977, the New York Times reported on the modernist’s new “passion” for antiques. “It’s embarrassing to like 18th-century French furniture,” Heller told the reporter. “Here I am, brought up on modern, falling in love with Louis XIV, Régence, and Louis XV.” That change of taste could have led him to an apartment designed by the Paris-educated Hastings. Or not. “My father liked to move a lot,” said Woody Heller, now a commercial-real-estate broker, who remembered a kind of Eloise childhood, with a hotel staff on hand. “It was a wonderful, full-service place to live,” he said. Property records show the Hellers were here in 1983 and 1984, and the next owner had come by 1987. The art and furniture in the listing seems to match what Heller had been collecting at the time — French Regency furniture, Asian antiquities — but his son said that it would have been unusual for his father to leave art. “We wouldn’t have left that all behind unless they weren’t real — but he didn’t tend to specialize in things that weren’t real.”

Asian antiquities flank windows out to the terrace off the great room.

Photo: Eytan Stern Weber/Evan Joseph Images

Other hand-me-downs could date back to the Brisbane era, since they’d probably have to be taken out via crane. (Contenders include a carpet sized for the massive great room, and a solid marble table.) The owner is selling those two pieces along with “English Regency tables, chairs, desk, and lamps; DeAngelis custom couches; inlaid marble table; artwork and sculptures from around the world,” according to the listing.

Price: $26 million ($20,381 monthly maintenance fee)

Specs: 4 bedrooms, 4 bathrooms

Extras: Wraparound terrace, three libraries, a formal dining room, gallery

10-minute walking radius: The Plaza Hotel, Central Park, Bergdorf Goodman, Café Boulud

Listed by: Michael Kotler, Douglas Elliman

On the southern end of the 45-foot-long great room are built-in shelves in the same dark maple as a formal study behind them.

Photo: Eytan Stern Weber/Evan Joseph Images

Behind the formal library, seen above, doors lead to a powder room and a more private office, where Brisbane might have conducted business. The current owners have turned it into a media room.

Photo: Eytan Stern Weber/Evan Joseph Images

The doors (left) may be antiques and lead out to the northwest corner of the terrace, with views up to Central Park.

Photo: Eytan Stern Weber/Evan Joseph Images

On the other side of the alcove in the great room is a dining room with solarium-style windows that can be lit from behind on the terrace. The room connects to the kitchen — the only one built for any upstairs units in 1926, when the building opened with hotel services downstairs.

Photo: Eytan Stern Weber/Evan Joseph Images

A romantic view into the great room. Columns and Gothic arches are typical of the Beaux-Arts style that Thomas Hastings was known for.

Photo: Eytan Stern Weber/Evan Joseph Images

A slim passageway off the gallery leads to bedrooms and a den.

Photo: Eytan Stern Weber/Evan Joseph Images

Off the other end of the gallery, a primary bed and bath have their own wing. The bedroom is 15 by 20 feet. Wood paneling hides four closets.

Photo: Eytan Stern Weber/Evan Joseph Images

Peer over Billionaires’ Row from the oversize tub in the primary bathroom.

Photo: Eytan Stern Weber/Evan Joseph Images

The hall at the other end of the gallery opens into a family den, with a bedroom on either side.

Photo: Eytan Stern Weber/Evan Joseph Images

One of the bedrooms.

Photo: Eytan Stern Weber/Evan Joseph Images

Another upstairs bedroom has private access to a staircase down to the kitchen, making it likely that it was designed for staff.

Photo: Eytan Stern Weber/Evan Joseph Images

A fourth bedroom is downstairs behind the library that’s now staged as a media room, and has a built-in desk.

Photo: Eytan Stern Weber/Evan Joseph Images