Decades of readings, performances, and fundraisers took place in this room, looking over the corner of Spring Street and West Broadway.

Photo: Russ Ross Photography for Corcoran

The dining table at the center of Ann Snitow’s Soho loft was rarely empty, and the food was never the point. The space was a “progressive mission control,” as the journalist Susan Faludi wrote, and “an establishment,” says Vivian Gornick, who remembered 165 Spring Street as “an atmosphere in which politics became friendship and friendship became politics, and the heart of our conversation was always feminism.” Friends, activists, and academics would sit to launch organizations, make protest signs, and, in one case, sculpt a 20-foot-long caterpillar chewing through a copy of the Constitution (it was a comment on the Patriot Act). “People were coming, going, sitting around the dining room table, eating and talking about activism, politics, and sex,” said Judith Levine, the feminist writer. “We sort of invented social constructivism there.” Sometimes, guests retreated to sleep on foldout cushions in the two-bedroom loft, then showed up again in the morning to talk over coffee. Visitors is the apt title of Snitow’s last book, a memoir that opens with a description of her home as “a boarding house for itinerant feminist organizers and experimental musicians.”

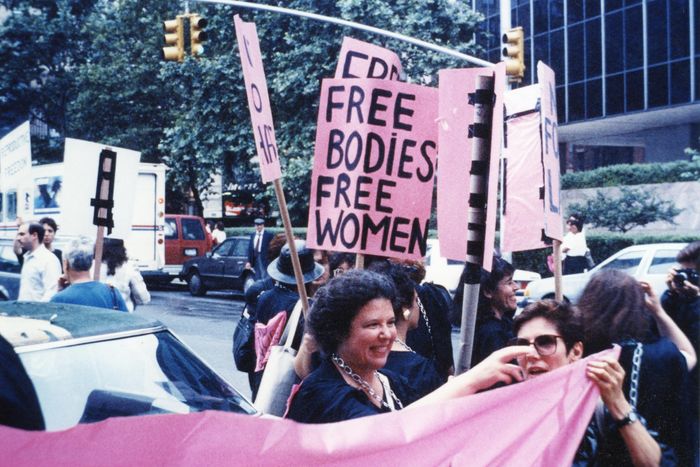

Snitow at a protest for No More Nice Girls, the organization that she founded with Levine. The signs were likely made at the kitchen table.

Photo: Tania Chelnov

Snitow started her career as an English teacher before launching gender-studies programs at Rutgers and the New School, where she taught for decades while writing, agitating, and founding feminist organizations devoted to free speech and women’s rights. She urged students to pursue what she called the “inside/outside life” and blend academics with action. She also welcomed her students into her home, greeting anyone who arrived in the same way, with an “Oh, tell me about …” Then she would listen. “I think a lot of people felt that she was their good mother,” Levine says.

Snitow’s dining table sat just in this space, on the left side across from the kitchen, for 40 years. “There were always people around it, except for maybe at eight o’clock in the morning,” said Levine.

Photo: Russ Ross Photography for Corcoran

Which made the loft their mother’s house. Or, as Snitow’s mentor, the psychologist Dorothy Dinnerstein, once described it, the apartment felt like “being inside of a beautiful woman.” The walls were painted in a fleshy terra cotta. Floors were covered in carpets. And bookshelves lined a whole wall from one side of the building to the other. There was nothing plain or dull about the place. Food was served on fine china picked up on travels. One closet was devoted to the souvenirs and gifts that Snitow couldn’t help buying, which included toys that could be pulled out for the kids who were sometimes part of the mix. And then there was the space itself — which started as an industrial box, before a 1984 renovation added curves and levels. The architects Jeff Milstein and Barbara Weinstein pushed the kitchen under an arched alcove, lifted a bedroom above a curving wall, and carved a private office into the living area that looks like a tiny southwestern house. Upstairs, the roof evolved into a garden where the writer Laurie Stone remembered sitting with Snitow and competing for attention with kids playing underfoot and “trees and plants blooming around us.”

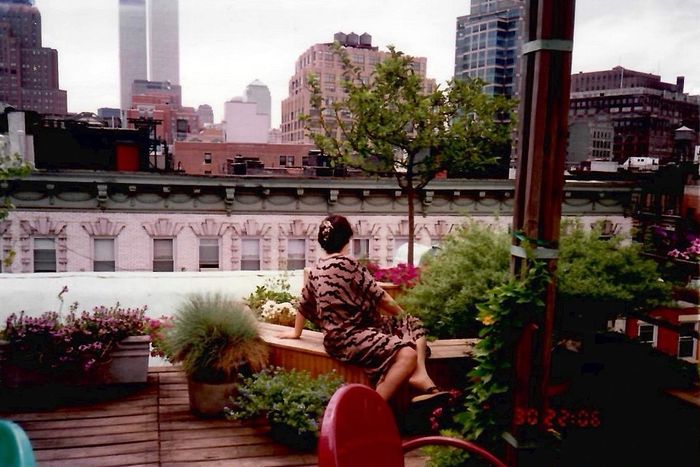

Snitow in the garden.

Photo: Tania Chelnov

When Snitow arrived in the early 1980s, the roof was plant-free. 165 and 167 Spring were industrial buildings where workers had made umbrella stands and dental equipment. Like the rest of the neighborhood, the buildings were taken over by the kinds of artists and writers who could hack it there. Snitow’s partner, Daniel Goode, was an experimental musician and composer who grew up on West 12th, went to the High School of Music and Art, and befriended artists who were already denizens of Soho. His world centered on sound, and he fell for Snitow through her voice — calling up WBAI after hearing her commentary on the program Womankind. On his walks around 165 Spring, he discovered that the cast-iron façades would ring like gongs used in Indonesian Gamelan music. So he started leading tours on the wonders of banging on the Isabel Marant store to elicit a perfect F. “I’m like a pied piper,” he told a reporter.

Goode and Snitow in the loft kitchen. They met in 1977.

Photo: Tania Chelnov

He sometimes led those followers to the loft, where Goode held rehearsals, hosted visiting musicians, and threw concerts that grew in size along with the apartment. In 2004, the couple bought the loft of their neighbor, whose wider space looked over the corner of Spring and West Broadway with windows on both sides. They now had a four-bedroom spread, and Goode had space big enough to rehearse a small orchestra and host public performances — like a recital of piano works by a Dutch composer that ended up on a critic’s list of memorably moving concerts. There were book parties. Fundraisers. Works of performance. Memorial services.

The loft they acquired in 2004 has a 35-by-32-foot great room. One memorable performance involved an artist who danced topless around the structural column, in imitation of an erotic dance.

Photo: Russ Ross Photography for Corcoran

Goode played clarinet, composed, and launched groups including an Indonesian Gamelan orchestra.

Photo: Tania Chelnov

“They both lived off the fuel of being in the middle of things,” says the couple’s niece, Tania Chelnov-Snitow. “I genuinely don’t know if they could have actually lived anywhere else.”

She started visiting as a kid with trips to family Seders and Thanksgivings, then solo trips in college that were always planned around her aunt’s meticulous date book, which Snitow would consult and say something like, “‘Ah, well, the Poles will be here, but you can come also,’” Chelnov-Snitow says. (The Polish houseguests started coming in waves after the fall of the Iron Curtain, when Snitow was flying back and forth to help dissidents across Central Europe fight anti-feminist governments, stock feminist libraries, and establish gender-studies programs.)

Tania Chelnov-Snitow on the roof on one of her visits to New York.

Photo: Tania Chelnov

Photo: Tania Chelnov

Snitow cut back on activities after being diagnosed with bladder cancer, instead centering her energy on finishing Visitors. Levine remembered a stop at 165 near the end of Snitow’s life. “We were all sitting at the table and she was wheeled out in a little secretary’s chair and she said, ‘I’m coming out to sit shiva with you.’” She died in August 2019. Goode moved into assisted living. The work of clearing out the loft has taken years — not just because the couple had four separate offices across the space, but because they also archived what they must have hoped were the seeds of a revolution. There were pamphlets, letters, book drafts, and a closet devoted entirely to the storage of protest signs, many that were likely made right at that dining-room table. Chelnov-Snitow donated it to Materials for the Arts. “I did not want that table to just get thrown out to who knows where,” she tells me. It ended up in Bed Stuy, at a nonprofit that uses art to educate kids. It was founded by a woman, a former English teacher.

Price: $6.995 million

Specs: 4 bedrooms, 4.5 baths

Extras: Private 2,175-square-foot roof-deck, three lofted sleeping areas, six walk-in closets, three offices

10-minute walking radius: Raoul’s, Film Forum, Mercer Street Books and Records

Listed by: Dan Fishman, Corcoran

At the front of the original loft (5W) on Spring Street, architects carved space in the living area for an office for Snitow. It looks like a small southwestern house and would have been painted a blush terra cotta when she lived here.

Photo: Russ Ross Photography for Corcoran

On the other side of that living area, a curved wall sits below a lofted sleeping area. Past that is the kitchen (in the alcove on the left) and the dining area (right, up the steps) where Snitow sat with feminist friends around a long table.

Photo: Russ Ross Photography for Corcoran

The back bedroom of the original loft (5W).

Photo: Russ Ross Photography for Corcoran

When the couple bought the apartment next door in 2004, they joined them through this vestibule. Crossing from one to the other means climbing a set of steps: The co-op straddles two 19th-century buildings that were joined.

Photo: Russ Ross Photography for Corcoran

Inside Snitow’s primary office.

Photo: Russ Ross Photography for Corcoran

Photo: Russ Ross Photography for Corcoran

A documentary crew filming in the loft.

Photo: Tania Chelnov

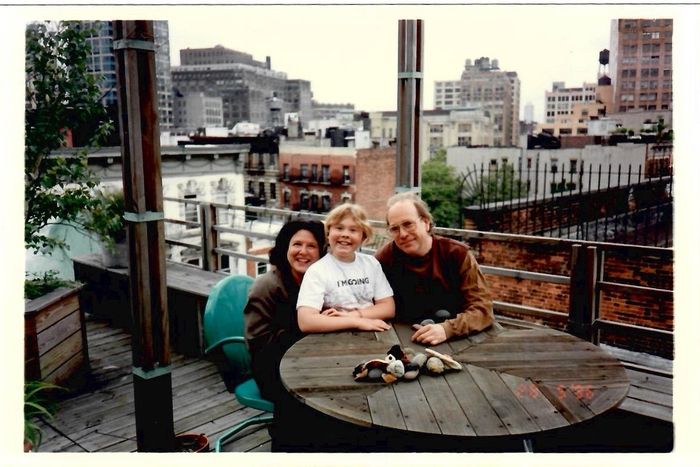

Family gathering before one of the couple’s massive Seders.

Photo: Tania Chelnov

In the back of the second unit is a lofted area for sleeping and a back bedroom, where guests could stay.

Photo: Russ Ross Photography for Corcoran

The couple negotiated to have private use of the roof of 165 Spring Street.

Photo: Russ Ross Photography for Corcoran

The roof was recently replaced, but the supports for a new deck remain for the next owner.

Photo: Russ Ross Photography for Corcoran

Photo: Russ Ross Photography for Corcoran