Photo-Illustration: Curbed; Photos: Walter Leporati/Getty Images, C. Taylor Crothers/Getty Images, Berenice Abbott/MCNY, Ted Thai/The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock, Alamy

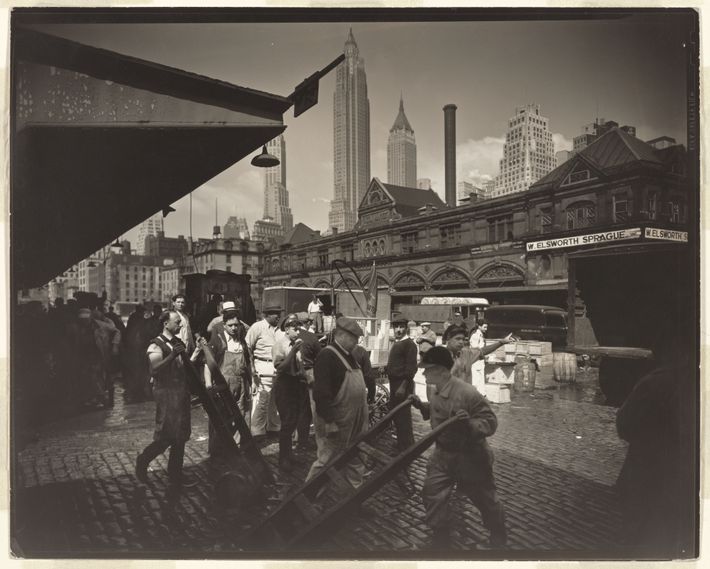

The photographer Berenice Abbott hung around the Fulton Fish Market in the mid-1930s, and the pictures she made show a city in mid-metamorphosis. In the foreground of one, men in high rubber boots tromp along a wet pier, some wheeling handcarts. You can practically inhale the mingled odors of brine, fish, and diesel fuel. This is the metropolis of muscle, the place that for four centuries had thrived on hauling, storing, packing, and shipping stuff. Above and behind that New York is another: a skyscraper horizon, hazy and distant, powered by the ability to move less tangible goods, namely money, trust, and ideas. Spearing the bright sky in Abbott’s background is the then new 70 Pine Street, a luxurious embodiment of the architectural and economic ambition that defied the Depression. (The Cities Service Company that had its headquarters there was literally the source of Manhattan’s energy. Its name later got shortened to Citgo.) It would take a world war and another generation for New York to complete the transformation from capital of trade to capital of capital. Eventually, the waterfront would go silent and the slender Art Deco office towers would be joined by blockier buildings. Abbott’s was a vision of the future.

Nine decades later, the FDR Drive has long since severed the piers from the high rises, and the contrast between those two forms of labor has given way to a catalogue of overlapping lifestyles. By the water, the Seaport has become a zone of leisure and consumption. The upland towers are increasingly havens of luxury living; 70 Pine was converted to condos a decade ago. Instead of selling fish or financial services, this new-old tip of Manhattan peddles experiences and souvenirs.

The Seaport is the part of Manhattan that still retains the most visible traces of the 19th-century mercantile hub and the one that is most vulnerable to 21st-century shocks. Climate extremes, financial meltdown, terrorist attack, pandemic shutdown — all have hit the Seaport hard, each time forcing it to question its core identity. And in addition to those periodic wallops, the Seaport suffers from a chronic sense of not being real. In warm weather, it’s a viewpoint, a bar scene, a concert venue (on the roof of Pier 17), a tourist magnet, and a nostalgic theater set. Then it spends the rest of the year forlornly waiting for summer.

The Seaport as Berenice Abbott saw it in 1936, with 70 Pine Street in the background.

Photo: Berenice Abbott/MCNY

That cycle has lasted decades, a past strewn with half-cocked plans, bankruptcies, struggling businesses, recriminations, and a neighborhood that refuses to give up on itself or surrender its personality. You can still go there, as Herman Melville did, and stretch your body seaward. When the wind blows in from the harbor, it brings a briny smell, like a ghostly memory of the fish market that long ago decamped to the Bronx. Every decade or two, the Seaport tries to rescue itself. Now there’s a new chapter in the offing, one that, to succeed, will have to overcome a long litany of disappointments. A tentative sense of renewal wafts through this battered corner. A new corporate overlord, Seaport Entertainment Group, has taken over control of the old fish-market blocks. The Seaport Museum has just expanded and looks fiscally stable. The fight over erecting a massive apartment tower in a long-vacant lot has been settled in the developers’ favor, though the building has yet to go up. And while the nearby Financial District’s diminished army of commuters can’t be relied on to keep bars and restaurants afloat, it’s being gradually replaced by a full-time population of residents. The neighborhood is looking up — but hopefully not like the prow of a ship just before it goes under.

It was a hardworking waterfront, redolent of fish and fuel.

Photo: Berenice Abbott/Courtesy New York Public Library

It took us 60 years to get to this. In the late 1960s, the craving for more — and more modern — downtown office space collided with the urge to hold on to what was rapidly being lost. The passage of the 1965 preservation law enshrined memory as a public good, but the midtown and lower Manhattan skylines were being hurriedly redrawn at the same time. It seemed as though another squat brick remnant came down every day, to be replaced by a bulky tower. The Seaport, with its still-functioning, mobbed-up fish business a few blocks from what Kurt Vonnegut called Skyscraper National Park, was the most dramatic battleground. Money needed room.

The city settled on a compromise: Knock down everything, except the pre–Civil War strip called Schermerhorn Row and a few other patches of obsolete real estate. The remnants would be handed over to a newly constituted South Street Seaport Museum, which had several old ships and a growing collection of artifacts but hardly any money — a combination that dogged it for years. The Times’ architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable was unimpressed by the prospect of gussying the working waterfront as a tourist attraction: “Here we go, playing preservation parlor games, on the way to the standard picturesque baloney of gas lamps and horse-drawn cars,” she wrote.

A Seaport crowd watches folksinging and dancing, 1973.

Photo: HUM Images/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

Eager to stabilize the museum’s finances and salvage the increasingly derelict, crime-ridden area, the city struck a complicated deal with the Maryland-based James Rouse Company. Rouse was selling the same solution that the company had already come up with for Baltimore’s Harborplace and Boston’s Faneuil Hall: a downtown shopping center — or, in the lingo of the early 1980s, a festival marketplace — with a rebuilt fish market, a pedestrian plaza on Fulton Street, a gaggle of vendor stalls, plenty of fried and sugary foods, and a generous helping of Huxtable’s picturesque baloney. Phase II was a new two-story mall constructed on Pier 17. The catch, as many preservationists saw, was that the festival marketplace depended for its appeal on a historical texture it simultaneously destroyed.

The Seaport was always a test of how well the contemporary metropolis could balance its bond with history and its faith in the future — a test it has mostly failed. “What preservation is really all about is the retention and active relationship of the buildings of the past to the community’s functioning present,” Huxtable wrote. “You don’t erase history to get history; a city’s character and quality are a product of continuity.” That conundrum shaped other neighborhoods too, but in those cases architectural holdovers lent themselves to new lives. Soho’s cast-iron buildings became useless as factories but proved perfect as artists’ studios and lofts. Some of West Chelsea’s massive industrial buildings were sturdy and spacious enough to morph into tech offices, art galleries, newsrooms, and photo studios. The Seaport, on the other hand, consisted of a jumble of rickety warehouses in need of radical overhaul. In the mid-aughts, the firm Cookfox threaded new construction through a block of 19th-century structures along Front Street, producing a handsome architectural quilt with nearly 100 apartments. But that project was the exception in an area where economic forces favored a mixture of erasure and neglect. The renewal attitude of the ’60s left only a random assortment of artifacts with punishing needs and scant market value.

Opening day at the Rouse Company’s South Street Seaport complex, 1983.

Photo: Ted Thai/The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Street performers outside the museum, 1985.

Photo: Alamy

The museum’s promised funding never materialized. Instead, the Seaport’s abundance of bars and its proximity to Wall Street gave it a frat-party vibe. In Preserving South Street Seaport: The Dream and Reality of a New York Urban Renewal District, James Lindgren quotes the reminiscences of a local resident: “the drunken yuppies … would find John Street a convenient place to piss, vomit, or copulate on the way to the subway.” Less inebriated New Yorkers stayed away, tourists followed their example, and a ham-fisted marketing campaign made things worse by selling New York’s original world trade center as if it were a leafy suburb. “One of a half-dozen television spots Rouse paid for in the summer of 1991 pictured an egg frying on a city sidewalk, a cooler waterfront, and the tagline, ‘The South Street Seaport, where New Yorkers go to get away from New York,’ ” Lindgren reports. Pier 17 turned out to be a slow-motion disaster, and Rouse eventually sold its Seaport holdings to General Growth, a few years before that company went bankrupt. (Baltimore’s Harborplace followed a similarly Hindenburg-ian trajectory; it’s now slated for demolition.) The Howard Hughes Corporation inherited control of the area and replaced Pier 17 with a strangely blocklike structure with restaurants on the ground floor (notably Jean-Georges Vongerichten’s the Fulton) and an outdoor concert venue on the roof. The company also floated an atrocious proposal to erect a 50-story apartment tower on the same pier, but that ambition thankfully dissipated. A separate plan to scrub the mercury from the site of a thermometer factory and build over it yielded Skidmore, Owings & Merrill’s design for a 26-story tower with 399 apartments — but the site, at 250 Water Street, still lies fallow and is up for sale.

After all that, the Seaport still belongs largely to a private for-profit company that sees it as a stage for its ambitions. That’s not a unique situation: NYU dominates the Village, and Columbia controls Morningside Heights. Real-estate companies accumulate large swaths of contiguous square footage: Vornado owns much of the area around Penn Station, Two Trees developed Dumbo, and Related created Hudson Yards. But those are all landlords. When Howard Hughes spun off the Seaport Entertainment Group last year, it entrusted this sizable chunk of Manhattan to a company with completely different DNA. SEG’s first CEO, Anton Nikodemus, had been president of City Center, the giant hotel–casino–condo–shopping-mall combo on the Las Vegas strip. Before that, he ran Bellagio.

“The two chief ingredients of renewal are destruction and irony,” Huxtable wrote in 1973, a remark that rattles around my brain as I talk to Nikodemus in a conference room with a view of the harbor that stretches from the Brooklyn Bridge to the Statue of Liberty. “This is an extremely authentic New York neighborhood,” he says. “So as a company, we’ve embraced that. One of our strategies on a go forward basis is how do we bring entertainment that really establishes a very vibrant energetic neighborhood within that authentic New York experience.”

What the Seaport has to offer an entertainment company — and what it offered SEG’s corporate predecessors — is verisimilitude: that fishy whiff of yore, the memory of slick cobblestones and sawdust on the floor, the ghost of the market that Abbott photographed in the ’30s and Joseph Mitchell eulogized in the 1950s. “The smoky riverbank dawn, the racket the fishmongers make, the seaweedy smell, and the sight of this plentifulness always give me a feeling of well-being, and sometimes they elate me,” Mitchell wrote in The New Yorker. And even his Seaport was a façade. Mitchell invented characters, condensed scenes, and embroidered dialogue, which is a reflection not only on his journalistic ethics but of the challenge of rendering a city that’s never quite as fixed or as true as its keepers would like it to be.

Among the traces of the maritime city here today, the ersatz takes many forms. The most lively echo of the old market is the artistic display of $29-a-pound black-sea-bass filets laid out on crushed ice in the Tin Building—a 1907 structure that was taken apart, redesigned (by SHoP and Roman & Williams), rebuilt in a different spot, and reopened in 2022 as a high-end food court run by Vongerichten. It’s not looking good: The Tin Building has hemorrhaged money (and helped sink SEG’s earnings) with its fancy-yet-basic restaurants, premium croissants, and shelves artfully stocked with strawberry gochujang. (The company says it’s now optimizing operations—that is, paring back the offerings to save money.)

Lunch hour at Pier 17, 1988.

Photo: Walter Leporati/Getty Images

The authentic New York experience is not the same thing as an experience of New York — it’s close to the opposite, in fact. History is just one ingredient in SEG’s cocktail of businesses, which is mixed according to what Nikodemus describes as a “30-30-30-10 rule”: equal portions of national chains (like Starbucks and Dunkin), well-established local names (Jean-Georges, for example), and promising newcomers, with 10 percent set aside for pop-ups and events.

Chief among the newcomers is Meow Wolf, which conjures fantastical, dreamlike places vaguely reminiscent of real ones. Founded in 2008 by an artists’ collective in Santa Fe, Meow Wolf has created immense environments, which resemble walk-in computer games or controlled acid trips, in Las Vegas, Houston, and Denver. A Los Angeles version is coming soon, and another will open at Pier 17 in 2028. (It won’t be alone; the whole genre of immersive experiences is already taking over vast tracts of Manhattan’s abandoned office space.) To Marsi Gray, the senior creative producer overseeing the newest expansion, tenant and landlord will make perfect partners. SEG is counting on Meow Wolf to bring in a steady, year-round torrent of visitors, and Meow Wolf hopes that SEG will surround its show in a kind of urban entertainment resort. “Seaport’s vision of becoming a destination for world-class experiences is a good match for us,” Gray says. Naturally, Meow Wolf wants such a fabricated hallucination to feel authentic, mostly by not having every component dictated from HQ. “We have a team of humans who do research on the local areas,” Gray continues, reassuringly. “We go into markets several years before we sign a lease and start our research into what’s happening artistically in the area.”

Flooding after Hurricane Sandy, 2012.

Photo: Timothy A. Clark/AFP/Getty Images

Good luck figuring that out in this hypercomplex global art capital. Meow Wolf’s talent scouts could visit the New Museum, say, or the Studio Museum in Harlem, the Whitney when the Biennial is on, or the hundreds of galleries representing thousands of artists. Someone might even point them to the radical, witty, genuinely New York–y immersive art experience Ruckus Manhattan, which Red Grooms created a few blocks away from the Seaport at 88 Pine Street … 50 years ago.

While SEG tries to conjure a new Seaport to match its corporate mission, it might be overlooking the neighborhood that already exists and that, if it isn’t exactly thriving, is at least starting to figure out how that’s done. (So long as another ruinous flood doesn’t wallop it again too soon.) It’s a pleasantly cut-off place, an island at the edge of an island with a population of tenacious loyalists who have hung on through 9/11, Hurricane Sandy, the pandemic, and an assortment of other downturns that always seems to leave more lasting damage here than in sturdier parts of the city. There are intimations of down-home prosperity, like horn blasts in the fog. An outpost of the independent bookstore McNally Jackson in Schermerhorn Row keeps the area’s literary traditions alive. A block down Front Street toward the Brooklyn Bridge is a new old-timey kind of place, Peck Slip Social, a five-month-old whiskey bar founded “by locals for locals.”

The glitzy new Pier 17, seen in 2020.

Photo: C. Taylor Crothers/Getty Images

The even glitzier new Meow Wolf.

Photo: Atlas Media

The future 250 Water Street as it will appear from the Brooklyn Bridge pedestrian promenade.

Photo: Courtesy Seaport Entertainment Group/SOM

Sitting at a high-top table with music turned low during a weekday happy hour, the bar’s founders, Alex Davis, an elementary-school teacher, and her partner, Learan Kahanov, a filmmaker, wonder whether SEG executives even know they exist. “There’s always been kind of an us versus them,” Kahanov says. “There’s the Seaport of the big corporations and, north of Beekman Street, there’s the little-shot mom and pops like us.” Kahanov moved to the neighborhood two decades ago, which makes him a relative newcomer. Davis describes herself as “born and bred down here when there was nothing. There’s still beauty and quietness here. It’s still a neighborhood, even though we don’t have a grocery store. I have no plans to go anywhere else.”

They’re getting company. A few blocks away, obsolete office blocks are being hollowed out, reskinned, and converted into residential buildings. The lot at 250 Water Street sits vacant, ready to receive its apartment tower. The stack of condos at One Seaport (a.k.a 161 Maiden Lane) stands forlorn and unfinished for now, since a three-inch tilt and a scrimmage of lawsuits brought construction to a halt. But eventually it too will house families in need of groceries and schools. “The perception is still that the Seaport is either touristy or vacant, but the reality is that it’s very residential now,” Kahanov says. All that growth is good for Peck Slip Social and bad for the tranquil vibe. Kahanov and Davis seem happy with that tradeoff.

Berenice Abbott long ago saw that the view from the fish market was a portrait of a bifurcated New York. That’s still true in the fully postindustrial parts of the city, though in a way that bespeaks new fissures. In the Seaport’s coming years, an ever-glitzier entertainment hub will coexist with a prosperous but fragile waterfront village. The two can wave at each other across the Beekman Street divide. Bedazzled visitors will blink in the glare from the water when they emerge from their Meow Wolf journey and stick around for a drink and a bite before heading to an uptown train. And maybe one day the Seaport will finally get a decent grocery store.