The technology department of the Peninsula school district in Gig Harbor, Wash., started stockpiling new student and staff devices as soon as the word “tariffs” began circulating, said district chief information officer Kris Hagel.

The 9,000-student district was already hearing from regular vendors who were saying they wouldn’t be able to hold the price for long. So to ensure the district could pay the same price it usually does for the devices, Hagel’s team rushed to get their purchase orders in.

“Our budgets are very tight,” he said. “We don’t have a lot of flexibility for changes in that.”

The Peninsula district isn’t alone in trying to avoid added costs. Other districts across the country are trying to purchase devices early, before President Donald Trump’s tariff plans cause steep price increases.

Trump on April 2 announced steep tariffs on nearly every nation, sending the U.S. stock and bond markets into a tailspin. Since then, he has walked back most of the steeper tariffs but has ratcheted up China’s. As of May 2, the tariff on goods from China stands at 145 percent, a 25 percent tariff applies to many goods from Canada and Mexico, and a 10 percent tariff on goods from most other countries is in effect.

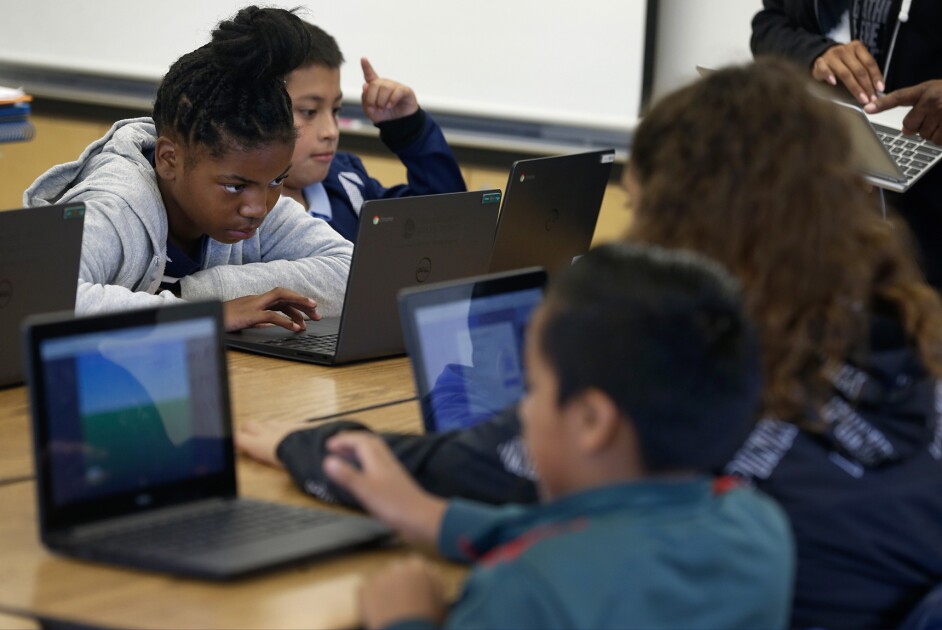

The tariffs are sure to affect prices of Chromebooks, iPads, and other electronics necessary to keep schools operating smoothly, experts say. Most of these items and their parts are made outside the United States and will be subject to those taxes.

They come at a bad time for school districts, many of which are “looking to make the biggest refresh decision that they ever have to take,” said Michael Boreham, the lead K-12 analyst for Futuresource, a market research consulting firm.

Districts, especially those that launched 1-to-1 computing programs at the start of the COVID pandemic, are now likely to be in the process of buying new student devices to replace the ones nearing the end of their useful lifespans, Boreham said. A typical lifespan of a Chromebook is between four to seven years. (Google recently extended software update support for some models to 10 years.) For iPads, the typical lifespan is around five to seven years.

If Trump’s levies continue as planned, Boreham predicts some districts might push back their replacement cycles and keep their current devices as long as they can. That is because districts are also dealing with the end of federal COVID pandemic-relief aid, which was used extensively to buy school devices. Other districts might have to discontinue their 1-to-1 computing programs.

Most school districts didn’t have 1-to-1 computing environments, in which every student has a school-issued learning device, until the pandemic led to emergency remote and hybrid learning, supported by billions in federal relief aid. Districts scrambled to purchase low-cost devices, most flocking to Chromebooks, which typically cost around $250 each. Others bought iPads, which typically cost about $400 each, or other brands of laptops.

In August 2019, less than a third of district leaders said they had 1-to-1 computing environments, according to an EdWeek Research Center survey. By March 2021, 90 percent of district leaders said they provide a device for every middle and high school student, and 84 percent said they did the same for elementary school students, an EdWeek Research Center survey found. As of February 2025, just 3 percent of educators said their school/district did not have 1-to-1 computing, according to the EdWeek Research Center.

Extending the length of device replacement cycles could be ‘problematic’

The problem is that these devices don’t last long in the hands of students, district technology leaders say.

Many districts replace their student devices every four or five years, said Hagel, the Peninsula district technology leader.

That district has had a 1-to-1 computing environment since 2018. (The devices were stored on classroom carts until the pandemic led the district to formally assign them to students.) Student and staff devices are on four-year replacement cycles, but they are set up so that 25 percent of their device fleet is replaced every year so it’s easier to manage the district’s technology budget, Hagel said.

Some districts, as a result of the tariffs, might think of extending their replacement cycles to five, six, or seven years. But that could be “problematic,” because after five years, the devices start to fail and fall apart, he said.

“Kids are rough on devices,” Hagel said. “They’ve got them in a backpack, and they throw the backpack, they drop their backpack.”

Another option is buying cheaper, lower-quality devices for students, especially if prices increase significantly, he said.

Chromebooks, iPads, and other laptops haven’t seen huge increases in price in the last seven years, according to district technology leaders. There may be small fluctuations every year, but prices have usually stayed the same.

“If there’s a 15 percent increase in [price]—which could easily be passed on [to us] with those tariffs—that’ll be a challenge,” Hagel said.

In the longer term, districts might have to rethink their 1-to-1 computing-program plans altogether, said Eva Mendoza, the chief information technology officer for the San Antonio schools in Texas.

For instance, in San Antonio, students are able to take home their devices. But if in the future the district isn’t able to keep up with the costs of a 1-to-1 computing program, Mendoza has proposed they be kept in the classroom, which will cut down on wear and tear. It wouldn’t be ideal, however, as most families rely on the district for a device and internet, she said.

Parents might have to pick up a bigger share of the costs of device repairs

Districts also have to take into account the costs of repairing devices from normal wear and tear between replacement cycles, district technology leaders say.

The tariffs are already affecting the cost of device parts, Mendoza said. The district usually puts in a large order for parts around this time of the year to get ready to repair student devices over the summer, but because of price increases, it ordered fewer parts this time around.

A third of district and school leaders say their school/district always pays the full amount of the repairs, according to an EdWeek Research Center survey. But 50 percent of respondents said students’ families pay for all or part of the repair costs.

If tariffs significantly increase the cost of parts, some districts might have to pass that cost to families, Hagel said.

Beyond the student and staff devices, districts also have to regularly upgrade other technologies that keep schools running, such as classroom interactive displays, paging systems, network switches, and internet infrastructure, district technology leaders say.

If the import taxes hold, Hagel said some of those other technologies might have to take a back seat or be scaled back, too.

“We have to stick with the most important things,” he said. “We have to get kids their devices. We have to get teachers their devices. We have to get the displays in the classroom and keep them fully functioning.”

Now is a good time for districts to reevaluate their 1-to-1 computing programs, especially those that scrambled to put them together at the start of the pandemic, Mendoza said. Districts’ technology and academics departments should be partnering strategically and asking questions, such as: What is the goal of our 1-to-1 program? Is this something that’s helping us meet our academic goals? Is this necessary in all grades?

“Our budget situation has been tight for a few years,” Mendoza said. “Now adding [increased prices] to our challenges—this might be a significant jump for us, so we’ll have to plan future years with pricing increases [in mind].”