Snøhetta’s new Far Rockaway branch of the Queens Public Library.

Photo: Jeff Goldberg/ESTO

Three curious things will strike you about the building at the intersection of Central Avenue and Mott Avenue in Far Rockaway: It’s an orange-glass box, it’s covered in a pattern of scratchy white swirls, and it parts at the corner like a slit skirt. It’s not clear at first what the building might be for, but you can’t mistake it for a house, a clinic, a funeral home, or a car dealership, and so by the time you’ve gravitated to the triangular portal, you’re not surprised to find out that it’s the Far Rockaway branch of the Queens Public Library.

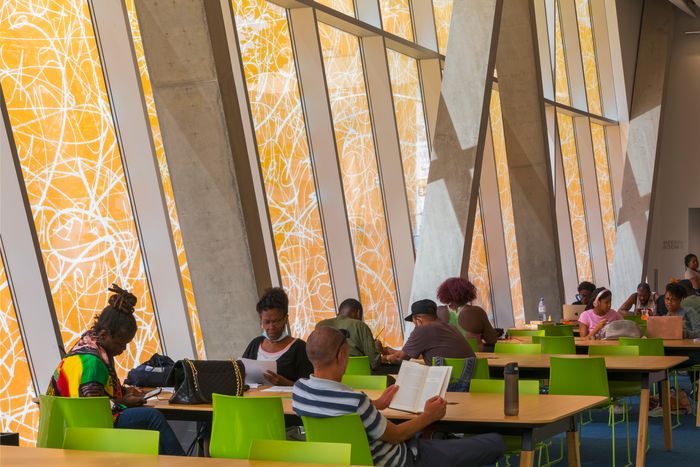

The two-story structure combines the deluxe and the whimsical, both rare qualities in this part of the city. Its oddness is part of what makes the building belong. Even on a gray day, it glows. Craig Dykers, who led the design team at Snøhetta, the architecture firm he co-founded, says that the color derives from the sunsets over the ocean a few blocks away. A set of indecipherable jottings on the glass, by the Brooklyn artist José Parlá, turns out to be pseudo-writing, happily abstract and content free, a representation of representation. At the nearest bus stop, passengers wait in front of that façade, and the scrawls seem to spring from their minds like cartoon speech that has burst free of its bubbles. So far, the walls remain unsmashed and untagged. “People protect what they love,” Dykers says.

The tinted glass walls give the light an amber glow.

Photo: Jeff Goldberg/ESTO

It takes a slow, deliberate process to cultivate that protective love. A library isn’t just a repository of print volumes or an all-purpose facility that helps users improve their English, file tax returns, or hunt for jobs. It’s also a neighborhood beacon, a place where kids at loose ends might stop off even though it doesn’t serve alcohol or fries. The Far Rockaway branch lures them into a glowing honeycomb of triangles, with V-shaped concrete columns and a staircase that cuts diagonally through the center, beneath an isosceles skylight. Folded metal pyramids hang from that segment of glass ceiling, diffusing the glare. It’s like a walk-in geometry lesson.

Light, too, takes various forms, flowing through the translucent walls to cast an amber glow or activating the dichroic-glass railings that change color as you pass. There are no dark or cut-off places here; from deep inside the second floor, you can look out to the street, down to the ground level, or up for a glimpse of clouds. The architects have designed away the opportunities to lurk. (Sunshine can be too much of a good thing; after the building opened, a library staffer buttonholed Dykers to complain about the persistent dazzle on her computer screen. He promised to figure out a solution.)

Snøhetta designed the building to welcome all, and that can create friction. The bar for keeping (or kicking) someone out is high, but on my visit, a man using a computer terminal suddenly began to yell and curse, and he kept up the loud threats as security guards escorted him to the street. Librarians also adjust the collection to match the flux in Far Rockaway’s demographics. Black and Latino visitors predominate, but on Friday afternoons a cohort of Orthodox Jewish children pack in before the Sabbath, emptying shelves of picture books like Yitzi and the Giant Menorah and A Synagogue Just Like Home.

At Far Rockaway, the metal origami on the ceiling is intended to diffuse sound; the dichroic-glass railings change color as you pass.

Photo: Jeff Goldberg/ESTO

Like most public projects, this one moved forward at a desultory pace, and the architects used the delays to study the institution, the neighbors, and the interaction between them to ask everyone they encountered what they hoped the building would do for them. Community engagement has become a watchword among city planners and architects, a necessary prelude to the construction of public projects. To hear Dykers talk about it, you’d think he didn’t design the library so much as draw a composite sketch of other people’s desires. Which prompts a question: How narrowly should a library be tailored for the neighborhood it serves? The pace of construction often lags behind the rate at which groups move in and out, elders die, and children grow. You can engage with the community you have but not with the one that will be around 15 years later, when the ribbon finally gets cut. In Far Rockaway, the result speaks well for Snøhetta’s approach: Consult all you like, then go away and come up with a design nobody would have thought to ask for, one that will strike anyone as a natural, even exhilarating place to be.

The new design for the as-yet-unbuilt New Lots branch of the Brooklyn Public Library offers a more targeted approach. An architectural team uniting the firms of MASS Design Group and Marble Fairbanks found inspiration in the sociologist Eric Klinenberg’s 2018 book, Palaces for the People, a study of how public buildings promote what he calls social infrastructure. In reviewing that book for the New York Times, a midwestern mayor by the name of Pete Buttigieg mused on how Klinenberg’s theories could be applied to concrete decisions about how to spend (and not spend) taxpayers’ money: “Social infrastructure becomes less a thing to maximize than a lens that communities and policymakers should apply to every routine decision about physical investment: Do the features of this proposed school, park or sewer system tend to help human beings to form connections?”

A rendering of the forthcoming New Lots library in Brooklyn.

Photo: MASS Design Group & Marble Fairbanks Architects

To help answer that question at New Lots, the Brooklyn Public Library hired the nonprofit agency Hester Street, which was founded in 2003 “to ensure that neighborhoods are shaped by the people who live in them.” That seems like an obviously virtuous goal, but it’s also a political one. A government agency (the BPL) is promoting change with one hand and stasis with the other. The architecture it’s embracing is fresh, forward-looking, elegant, and sensitive, but it is also designed to express an explicitly race-based narrative for the benefit of New Lots’s current population. (Hester Street shut down last summer, shortly before the White House started treating its reason for being as an evil spell: The organization, its valedictory note read, “worked to advance racial equity and economic justice through projects focused on access to open space, community ownership, civic engagement, environmental justice and climate resilience, justice reform, education, arts and culture, and so much more.” That’s the kind of language that makes Stephen Miller writhe in his coffin.)

Neighborhoods change. Priorities shift, longtime residents move out, economic patterns get disrupted, and institutions move on, leaving their husks behind. The white farmers who settled New Lots in the 1820s left few traces except for the graceful New Lots Reformed Church, which cost them a lot of free labor and a total of $35. It still stands across New Lots Avenue from the library, a city landmark and the home of a small African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church congregation. The neighborhood is now majority Black, and so it resonated when, in 2013, archaeologists determined that the earth beneath the library’s playground had been the church’s original cemetery and contained the remains of many 19th-century Blacks. Hester Street consultants asked New Lots residents to help translate that ancestral history into three-dimensional form. For starters, the playground was renamed Sankofa Park (from a Ghanaian concept of moving forward while honoring the past) and redesigned.

An exterior rendering of the BPL branch at New Lots.

Photo: MASS Design Group & Marble Fairbanks Architects

The commemorative impulse also imbues the plan for a new library adjacent to the playground. Motivated by neighbors’ responses, the architects produced a flowchart studded with the imperatives of uplift: Invite, Empower, Reflect, Acknowledge, Celebrate, Liberate. They then mapped those stages of an imagined transformational journey onto specific design elements. The central feature is a mass-timber column that branches into ceiling ribs, an indoor urban form of the palaver tree where villagers in West Africa gather to resolve conflicts. A trophy staircase leads down to a double-height open room with a wall that will be emblazoned with a narrative about the burial ground. The glass-sided building will be shrouded in a pixelated wrap made of metal slats — similar in concept to the veil enclosing the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. — some of them inscribed with epigrams by Black leaders. The roof terrace offers a view over the commemorative park.

What all these details add up to is a building and landscape conceived together and joined in purpose to give library users a way to absorb history into their ongoing lives. The design delivers an exhortation: Remember, but move on; move on, but keep remembering. It’s a message that suits architecture, which is constantly negotiating between the city it finds and the one it shapes, between the interpreted past and the wished-for future.